The New Standard for US GAAP

Historically, digital assets were treated as intangible assets. Pre-December 15, 2024, and to the disdain of digital assets proponents, changes in fair value could only be reflected to the downside (as impairment), with no upward revaluations allowed.

However, with the implementation of ASU 2023-08 (Subtopic 350-60), certain crypto-assets would now be available for upward revisions in digital asset fair values on the balance sheet, with changes in Fair Value reflected in the Income Statement. ASU 2023-08 still requires measurement at fair value under ASC 820, meaning market-based exit price assumptions, not cost-based or intrinsic value models.

The changes applicable to all assets that meet all the following criteria:

- Meet the definition of intangible asset as defined in the FASB Accounting Standards Codification®

- Do not provide the asset holder with enforceable rights to or claims on underlying goods, services, or other assets

- Are created or reside on a distributed ledger based on blockchain or similar technology

- Are secured through cryptography

- Are fungible

- Are not created or issued by the reporting entity or its related parties.

Key Changes for Public Companies

SAB 122 – Rescission of SAB 121 (Crypto Custodial Obligations)

In 2022, the SEC issued SAB 121, requiring entities safeguarding crypto-assets on behalf of users to record those assets and related obligations on their balance sheet, even when they didn’t legally “own” the assets, they were just holding them on their customers behalf. This created significant controversy, particularly in the crypto industry, where such treatment diverged from traditional custodial accounting under U.S. GAAP.

However, with the issuance of SAB 122 on January 23, 2025, the SEC formally rescinded SAB 121, removing the requirement to recognize safeguarded crypto-assets and offsetting liabilities on the balance sheet. The updated guidance instead points companies back to existing GAAP, specifically ASC 450-20, which governs accounting for loss contingencies.

Under SAB 122, entities must now evaluate custodial arrangements using a contingency framework, recognizing a liability only if a loss is probable and reasonably estimable. If that threshold isn’t met, no liability or asset is recorded. Yes, that means customer assets and an associated liability do not have to be on a crypto-companies balance sheets. While balance sheet recognition is no longer required, robust disclosure is still encouraged, particularly when safeguarding large volumes of crypto-assets on behalf of customers.

Companies previously affected by SAB 121, such as exchanges, wallet providers, or custodians, should apply full retrospective adjustments, removing previously recorded custodial assets and liabilities, and adjusting retained earnings accordingly.

Crypto Accounting and Audit under US GAAP

Now that we understand the basics of US GAAP, we can now move on to how we can actually audit crypto assets and associated activities.

Once the auditor understands what digital assets they are testing and how many are expected, they can begin to apply the auditor’s assertions to begin testing:

The Balance Sheet

- Completeness:

- Existence

- Valuation

- Rights & Obligations

- Presentation & Disclosure

The Income Statement

- Completeness

- Occurrence

- Accuracy & Valuation

- Cutoff

- Classification

- Presentation & Disclosure

Note on the Statement of Cash Flows:

Digital assets are “non-cash” items, and therefore should be treated as such on the statement of cash flows. Even stablecoins are typically not considered “cash”. Therefore, this can make auditing the statement of cash flows particularly tricky, especially if the company is operating with and using stablecoins to receive revenue and pay for expenses. The auditor should be particularly diligent when auditing the Statement of Cash Flows with this in mind.

Enter Proof of Reserves

The concept of Proof of Reserves (PoR) was introduced in response to the 2013 Mt. Gox collapse, a watershed event that underscored the urgent need for transparency in the cryptocurrency space. Originally, PoR was used by crypto exchanges to demonstrate that they held enough assets to fully support user balances. Since then, its application has expanded considerably. Today, PoR is also used to verify holdings behind a broader array of digital financial instruments—such as stablecoins, asset-backed tokens, and exchange-traded funds (ETFs)—as part of broader efforts to build trust and promote financial integrity within the ecosystem.

Since around 2018, independent attestations conducted by public accounting firms have become the accepted norm across the digital asset industry. These engagements are generally performed under internationally recognized standards—ISAE 3000 for global contexts, and AT-C 205 in the United States.

It’s important to note that these attestation engagements are not equivalent to full audits of financial statements, nor are they meant to be. A comprehensive financial statement audit involves examining the entirety of an entity’s financial health, including the balance sheet, income statement, cash flows, and accompanying disclosures. These audits are often time- and resource-intensive, typically occurring on an annual basis and requiring months of work from both the company and its auditors. Moreover, unless the entity is publicly traded, the audited financials are not usually released to the public.

In contrast, Proof of Reserves (PoR) attestations are more focused in scope. They aim to provide assurance on whether specific assets—such as those backing exchange customer balances, stablecoin liabilities, tokenized assets, or ETF units—are fully supported by appropriate reserves. While these engagements apply the same professional scrutiny as a financial audit, they are limited in scope to reduce complexity and enable more frequent reporting. This narrower focus eases operational burdens while still delivering meaningful transparency to stakeholders.

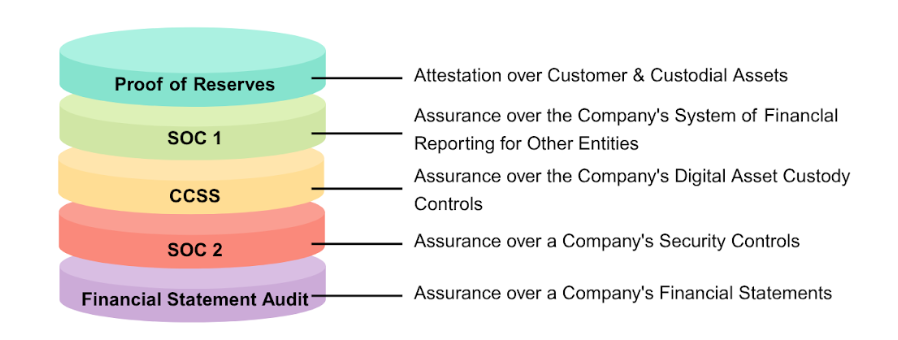

Conclusion: A Layered Approach to Assurance in a US GAAP World

As the digital asset industry matures, regulatory clarity and technical assurance must evolve in tandem. Recent developments—such as ASU 2023-08 and SAB 122—signal a landmark shift in how crypto is accounted for under US GAAP, moving from legacy impairment models to fair value and from overstatement of custodial liabilities to principles-based judgment.

Together, these layers form a complete assurance architecture—anchored by US GAAP compliance but enriched by crypto-native innovations like Proof of Reserves. For CFOs, controllers, auditors, and industry leaders, understanding how these layers interact is critical to building sustainable, transparent, and trustworthy organizations in the digital asset space.